Power Naps Post

Volume 1 Number 1 June 2023

In this issue

C&G Artpartment Harcourt Road Art Project

Lyra Garcellano Zombie Scrolling, Infinite Looping

Cédrick Nzolo & Dominique Malaquais Molili Mabe My Other Life & Postscript

Wing Chan Banana Box Bears

POWER NAPS NOTE

A strange dream came to me a couple of months ago. It is about two mole friends, one of them is myself, zigzagging our ways in the dark earth. When beams of light come through, we throw capers up into the air and go on digging our ways. Repeat. Like many dreams, this one was enigmatic. I could only think of two hints. The dream arrived when I started to articulate the idea of Power Naps Post to artist friends who write. Meanwhile, I was rereading Etel Adnan’s Night, at the beginning of which she quoted Thelonious Monk, ‘It’s always night, otherwise we wouldn’t need light’.

It is fascinating to include the English translation of my little airport’s 2018 lyrics to ‘You said we’d be back’ in this issue, with the help of Michelle Wong. Lam Ah P’s words draw our attention to the repeated signals of the howling wind, fwoosh fwooshhhh wooshhhhh. It is a wind that speaks about distance, though it is ambiguous whether ‘I’ am moving forward or holding back. On the other hand, Clara and Gum of C&G have moved on. They relocated to England, settled their family, and restarted their Artpartment in Sheffield. They try to overcome distance through remembrance. In their article, Clara and Gum call for stories of multiple Harcourt Roads and highlight the importance of archiving for justice. Manila-based artist Lyra Garcellano makes explicit the worries of C&G. In text and toons, she interprets napping as the potential path to invisibility and dormancy in the attention economy maps. Paradoxically, the fear of napping also triggers the desire for elsewhere. Photographer and designer Cédrick Nzolo owes himself to the circumstances of severe, daily power outages that are part of the social reality and political violence in Kinshasa, a city in the same time zone as London. Cédrick’s letter to the late scholar Dominique Malaquais (1964–2021), who had translated his rage, despair, and hope a decade ago, has activated memories and dreams. Here I am grateful to Adeena Mey for his generous help with the French-to-English translation. In yet another dreamscape, I travel with a banana box. I imagine its built-in ventilation holes being the portals to another world of rage, despair, and hope: Istanbul. Imagine the banana box as the sign for solidarity and change, where it would shapeshift into the figure of a civil society carried, transported, and shipped away by cultural workers.

Some of the artist friends I approached became the contributors to this issue of Power Naps Post. Now that their writings and translations are in place, it does feel like they are dots of capers marking various light sources as we move through the landscape. Like many publications in Hong Kong, Power Naps Post is interested in language. You will find some texts in English and Chinese, others vernacular Cantonese only, and still others English only. I would like to believe that the choices of language are doing justice to the respective contexts and places that the texts inhabit.

—Wing Chan

《叉電報》

第一期 2023年六月號

今期內容:

C&G藝術單位〈夏慤道藝術計劃 〉

Lyra Garcellano〈低頭族,離神滾動,無限循環〉

Cédrick Nzolo & Dominique Malaquais〈無光行履:我的別種生活〉及後記

陳穎華〈香蕉箱日記〉

編者的話

幾個月前我發了一個不尋常的夢。夢中,兩位鼴鼠朋友在黝黑的境域中撥土前行,其中一個是我。 每當光束透入黑土,我們便揮掌將酸豆拋向空中,然後繼續挖掘出路,不斷重複。這個夢異常神秘,我想到兩個解夢提示。其一,發夢前後我開始跟藝術家朋友談到《叉電報》的概念。其二,我當時正重讀已故黎巴嫩藝術家 Etel Adnan 的長詩《夜》,她在書的開端引述爵士樂手Thelonious Monk的話:「不擁抱黑夜,便看不見光」。

今期內容由 my little airport 於2018 年發表的歌詞〈你說之後會找我〉展開。我與Michelle 黃湲婷一起把歌詞翻譯成英文。林阿P 的文字不停發放風的信息,聽到呼呼呼呼呼呼呼呼,我們想起朋友在遠方的呼喚,但「我」在風中前行或是後退,確實說不清楚。而C&G 明顯在風中前行。Clara 和阿金舉家搬到英國,安頓好家人後,在錫菲重新開始他們的藝術單位,再次與地方連結。他們的「夏慤道藝術計劃」目的是記錄不同城市中的夏慤道故事,以文獻存檔爭取話語正義,用記憶克服距離帶來的挑戰。駐馬尼拉的藝術家 Lyra Garcellano 彷彿感受到C&G離鄉的憂慮。她將「叉電」詮釋為一個休眠和隱身的狀態,並強調在注意力經濟的角度來看,這狀態對藝術家甚為不利。有趣的是,這種恐懼同時為人帶來不顧塵世、對別處的嚮往。駐金沙薩的攝影師兼設計師 Cédrick Nzolo 嚮往書寫,但日常的大規模停電考驗他的耐性。十多年前,學者Dominique Malaquais (1964–2021) 翻譯了Cédrick的散文詩,他藉此記錄了自己因社會現實和政治不公而來的憤懣、絕望和願望。現在,Cédrick寫下後記悼念Dominique,又因此重新燃起了種種回憶和未完成的夢想。感謝Adeena Mey幫忙將法文書信翻譯成英文。最後,我藉着一個香蕉箱抵達同樣面對着嚴峻社會現實及政治不公的伊斯坦堡。由香蕉箱的獨特開孔設計,我們思考公民社會的作用和文化工作者的角色。

當然有比喻的成分,但一眾為本期撰稿的作者和譯者也許就是我的鼴鼠朋友,他們的文字作品猶如那些被拋向空中的酸豆,標記着我們穿越風景時體驗到的各種光源。最後,《叉電報》跟其他在香港出版的刊物無異,要考慮到語言。讀者會在《叉電報》見到中英雙語的文章,或者只限廣東話和只限英文的文本。語言的選擇包含了對文本背景和地域的思考。

——陳穎華

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[詞 Lyrics] [中英雙語 CANTONESE & ENGLISH TRANSLATION]

你說之後會找我

詞:林阿p (my little airport)

你在哪裡/我竟不知/枉我們曾每日都相對/你想著誰/為何流眼淚/我竟也不再問一句/呼呼呼呼/呼呼呼呼/像風一樣的年歲/呼呼呼呼/呼呼呼呼/已不知被吹到哪裡/我在哪裡/我也不知/像被迫進了一個監獄裡/只有過去/已沒能再聚/目睹最美的事粉碎/呼呼呼呼/呼呼呼呼/像風一樣的年歲/呼呼呼呼/呼呼呼呼/已不知被吹到哪裡/一生人很短/但終點很遠/任年月讓我再大多幾歲/任年月伴我繼續老去

YOU SAID WE’D BE BACK

Where are you now / How could I not know / I can’t believe we used to see each other every day / Who were you missing / Why did you cry / How did I learn to not ask you anymore / fwoosh fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / Time passes by like the wind / fwoosh fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / I don’t know where the wind has brought me to / Where am I / I also don’t know / As if I’m forced into a prison / There is only the past / There is no meeting between us again / Witnessing things beautiful shattering into pieces / fwoosh fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / Time passes by like the wind / fwoosh fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / fwooshhhh wooshhhhh / I don’t know where I’m carried to / Life is short / But the destination is a long way away / Let the time pass and let me grow / Let the days pass and keep me company as I keep growing old

Original lyrics by Lam Ah P; English translation by Wing Chan & Michelle Wong

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[香港藝術搜索頻道 Hong Kong Arts Discovery Channel] [只限廣東話 CANTONESE ONLY]

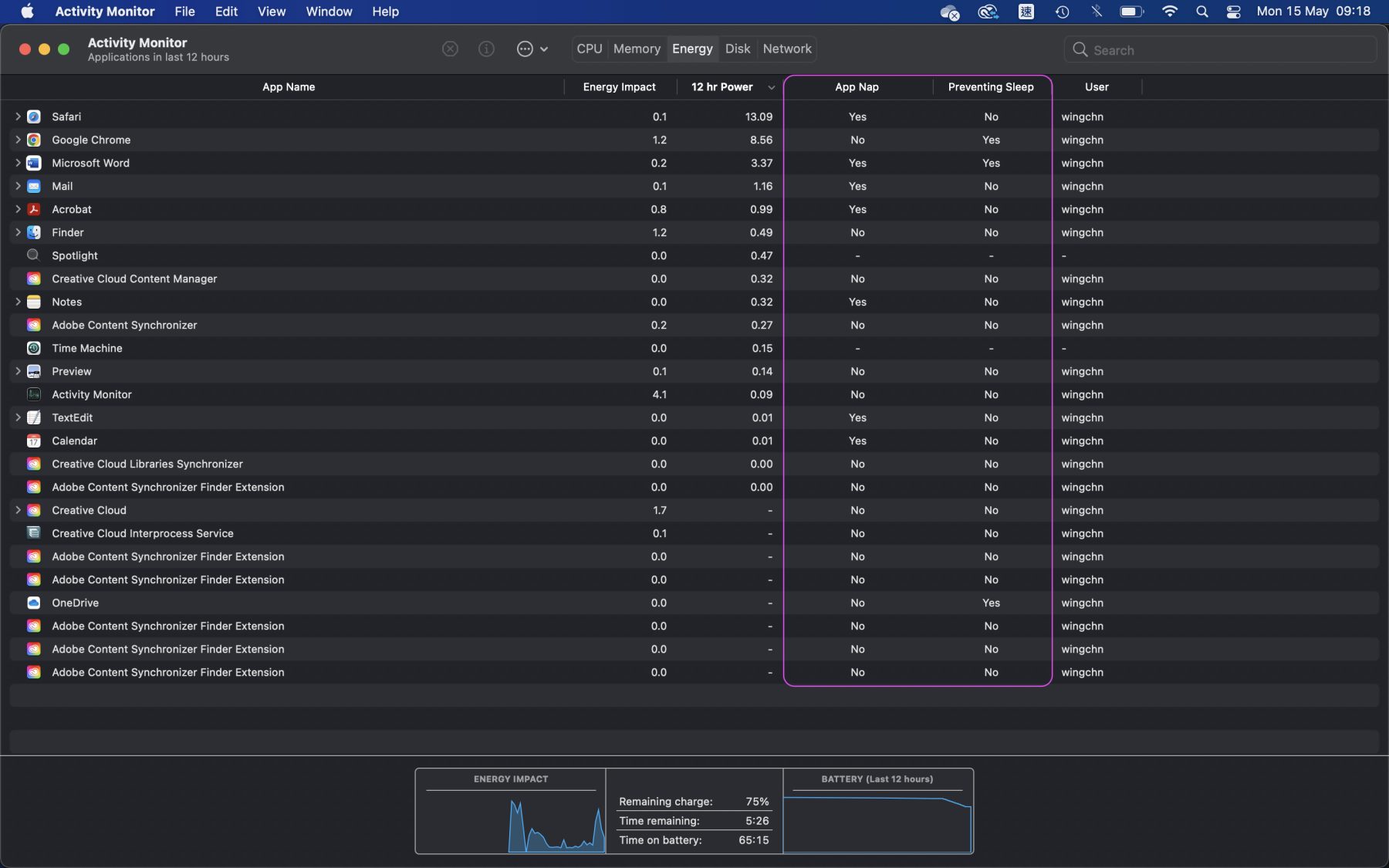

在Google地圖搜尋香港夏慤道之一。由 C&G 提供|Searching for Hong Kong’s Harcourt Road on Google Map I. Courtesy of C&G

在Google地圖搜尋香港夏慤道之二。由 C&G 提供|Searching for Hong Kong’s Harcourt Road on Google Map II. Courtesy of C&G

在Google地圖搜尋香港夏慤道之三。由 C&G 提供|Searching for Hong Kong’s Harcourt Road on Google Map III. Courtesy of C&G

夏慤道藝術計劃 HARCOURT ROAD ART PROJECT

文:C & G 藝術單位

C & G藝術單位喺今年(2023年)策劃咗一個關於夏慤道( Harcourt Road )嘅藝術計劃,雖然呢個計劃喺英國開始,但係,呢個計劃概念上嘅起點都係源自香港。

由2011年8月香港政府總部搬去金鐘夏慤道開始,夏慤道係好多嘢嘅靈感來源,尤其係「抗爭」。佢畀到我哋好多想像空間,如果唔係都好難出現2014年雨傘運動、2019年反送中運動。

話時話,夏慤道都算係香港咁多街道裏面其中一條比較特別嘅街道,佢嘅中文名就用咗一個比較少用同難讀嘅「慤」字,而且我哋搵到夏慤道嘅街名牌裏面,係有三個唔同嘅慤字:「愨」、「慤」、「𢡱」。一個街名,三個寫法,你話畀到我哋幾多想像空間呢?

喺近十幾年歷史裏面,夏慤道好似同抗爭連埋咗一齊咁。當我哋喺英國錫菲,第一眼見到一條同名嘅Harcourt Road嘅時候,原來都會不期然諗到香港夏慤道嘅畫面,可能呢啲就係叫做「諗多咗」啫。之後清醒啲再經過錫菲Harcourt Road,就嘗試了解番呢條Harcourt Road係咩料先。原來,佢都有自己獨特嘅歷史同經歷。

根據錫菲夏愨道街坊會提供嘅資料[1],喺18 世紀初,呢條街係處身一個共享土地(Common Land)嘅區域入面,即係大家共同擁有、分享呢個地方,大家基本上可以自由進出、放羊,甚至耕田。當然,名義上,呢啲都係帝皇嘅地。再翻查資料,「共享土地」嘅出現,其實係因為有啲地嘅生產力比較低,於是就無人耕[2]。不過,雖然瘦田冇人耕,但原來都好有用:當「肥田」要休息嘅時候,農夫就會帶佢哋飼養嘅動物去呢啲「瘦田」度搵食,慢慢變成大家共識嘅「共享土地」。夏愨道街坊會提供嘅歷史概覽,字裏行間都對「共享土地」買少見少呢個現況有啲惋惜。雖然係咁,其實英國仲有「共享土地」㗎!不過而家嘅「共享土地」有好多法律條文規管,同從前嘅「共享土地」相對自由奔放嘅本質,好唔一樣。好在,近來多咗有心人,倡議重新重視呢個「Common/Commoning/共享」嘅精神。例如,共享土地基金會(Foundation for Common Land) 喺2006年成立[3],目的就係邀請更多公眾人士關注同關懷英國嘅「共享土地」,仲有好多在地嘅行動,將「共享」精神發揚光大!

錫菲夏愨道街坊會仲同我哋分享:喺1970年代嘅時候,由於錫菲大學想擴充,就喺夏愨道買咗啲屋,而且仲用一啲地產商慣常用嘅方法,故意長期空置買入嘅單位,令到附近死氣沉沉,繼而令周邊街坊喺半推半就嘅情況下賣埋自己嘅屋搬走。好在,街坊正正因為咁,反而更加團結,佢哋聯同起嚟去搵大學理論,最終大學冇直接喺度擴建校舍,而係將買入嘅物業變成學生宿舍。後來喺2000年,大學決定賣出夏愨道旁邊嘅物業,又令街坊頭痛起嚟。結果,街坊成功游說到大學唔好將物業賣畀發展商!後來,主要買入呢啲物業嘅都係小家庭同小業主,令到成個社區嘅整個面貌都多啲生氣。

我哋喺英國做「夏慤道Harcourt Road」展覽,當然想幫自己「叉電」,乘機借助地球上另一條夏愨道,幫自己諗出路。錫菲夏愨道,叫我哋唔好忘記大型社會運動入邊,嗰種團結、共享嘅精神,大家一齊嗌、一齊衝、一齊退… …雨傘時有,2019年更多! 當年,大家有無拗撬?一定有,但係我哋都一齊踏出咗嗰一步。咁下一步可以點?無計,開咗個頭,惟有加啲油,再行落去!當年夏慤將軍代表香港接受日本二戰後嘅投降,我吔相信,香港人同多個版本嘅「夏慤道」,夾埋一齊「叉電」, 一定會產生好正嘅化學作用!

有啲人係熄機先可以叉電,有啲人係開住機叉電,C&G我哋,都唔後生,有返咁上下歷史,雖然未out,但一定唔係新型號,似乎要運作緊先可以叉電,即係: 慢叉!既然「運作緊」先叉到電,大家幫我哋叉叉電吖:我哋而家收集緊「夏慤道Harcourt Road」上關於「自由」嘅個人故事,希望有機會將香港、錫菲、甚至世界其他地方有關夏慤道Harcourt Road嘅故事記錄低,作為文獻保存,同時,亦準備令某種化學作用蓄勢待發!

期待睇到大家嘅故事!故事可以send去harcourtroad.art@gmail.com。

註:

[1] 錫菲夏愨道街坊會Harcourt Road Community。詳見 http://www.harcourtroad.org.uk/history

[2] 共享土地註冊機構協會Association of Commons Registration Authorities。參考 https://www.acraew.org.uk/history-common-land-and-village-greens

[3] 共享土地基金會Foundation for Common Land。詳見 https://foundationforcommonland.org.uk/a-guide-to-common-land-and-commoning#what-are-commons-banner

C&G嘅「夏慤道Harcourt Road」展覽由Bloc Projects委約支持。

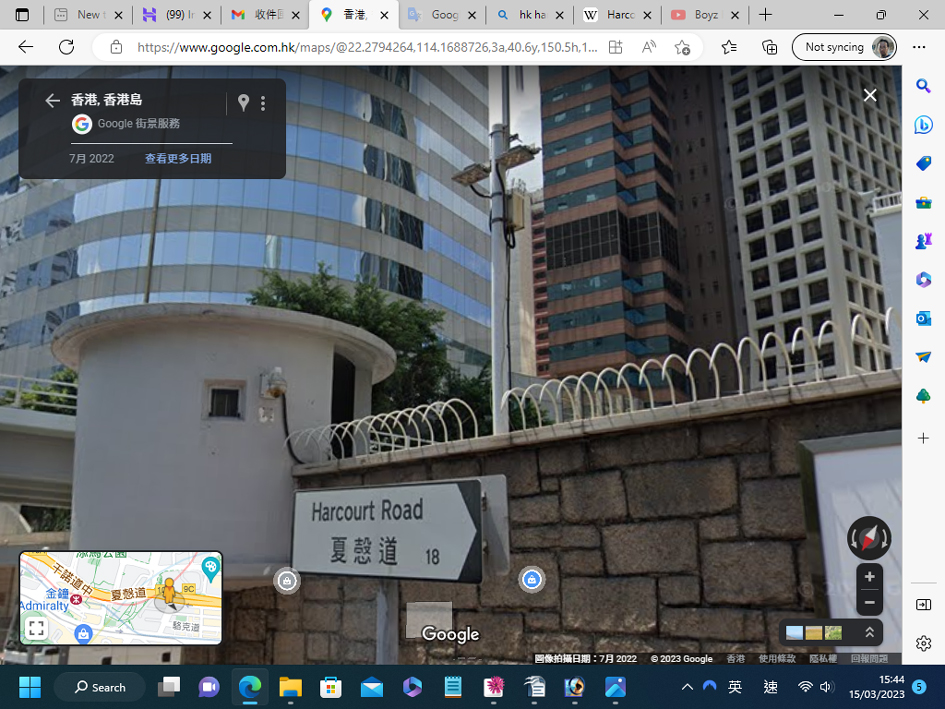

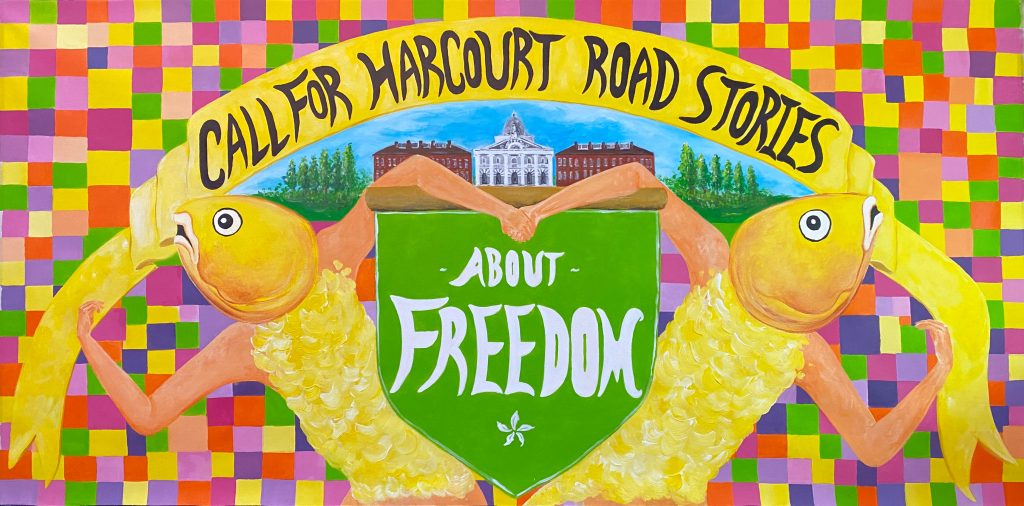

張嘉莉,《盧亭收集夏愨道故事橫額II 》,2023年,塑膠彩布本 | Clara Cheung, Lo Ting Calling for Harcourt Road Stories Banner II, 2023, acrylic on canvas, H. 90 x W. 180 cm

Clara話:

2021年,為咗避開政治打壓,同埋繼續自由發聲,過咗嚟英國,亂打亂撞去咗參觀曼城嘅人民歷史博物館,見到好多英國以往嘅政治橫額。好鍾意當中用嘅符號,好想可以再了解多啲呢度嘅橫額製作歷史,亦都想畫一系列以香港神話人物:盧亭為主角嘅橫額。

Clara says:

In 2021, I relocated to the UK, to flee from political persecution in Hong Kong. I had a chance to encounter a series of political banners at the People’s History Museum in Manchester. Fascinated by the rich history and iconography of political banners in the UK, I want to further study the visual language of these banners and develop a series of banner-paintings for Lo Ting, the mythical ancient symbol of Hongkongers.

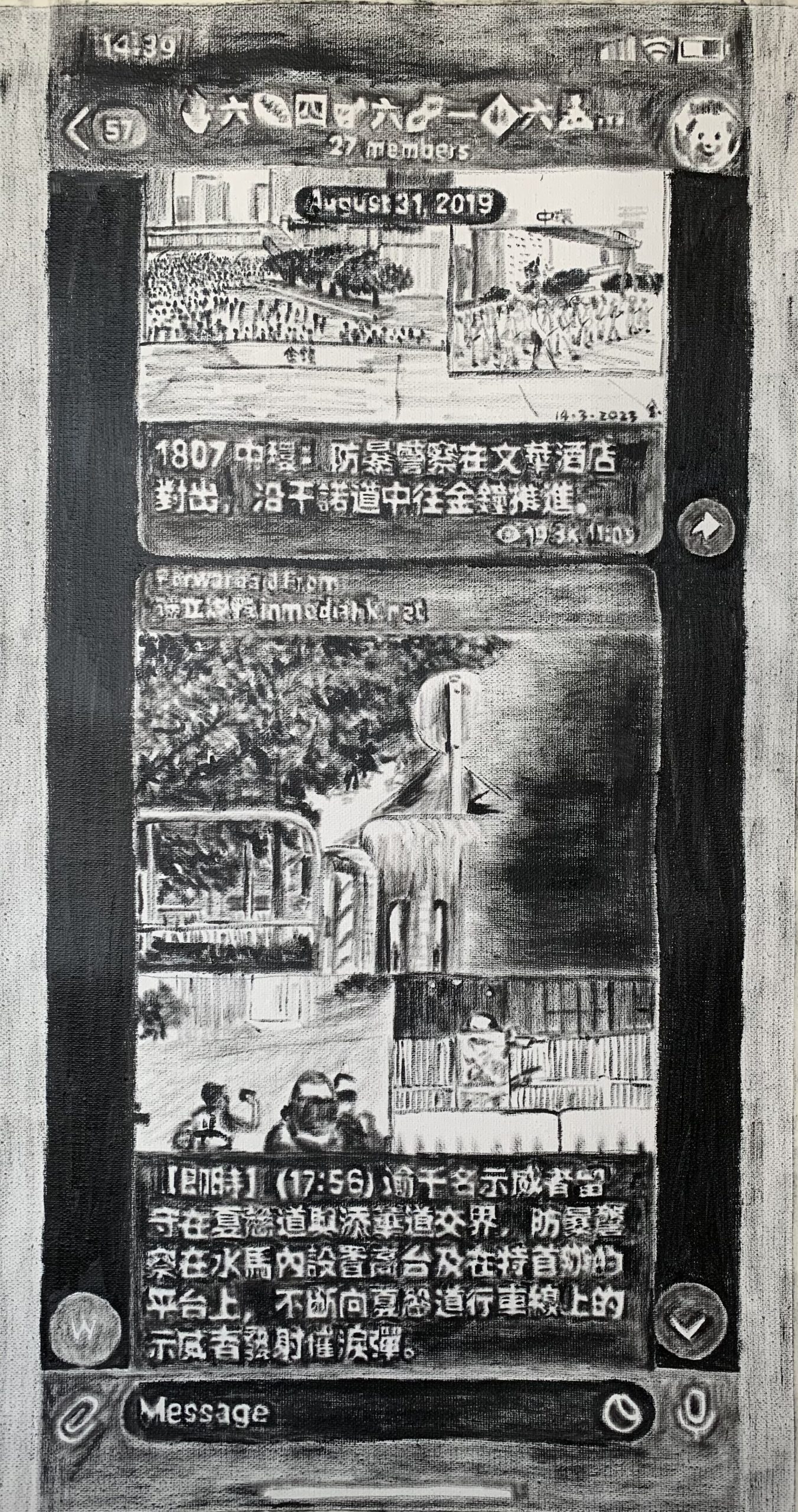

鄭怡敏(阿金),《2019年8月31日私人Telegram》,2023年,油彩布本 | Cheng Yee Man (Gum), Personal Telegram 31 August 2019, 2023, oil on canvas, H. 64 x W. 34 cm

作品介紹:

~ 1807 中環:防暴警察在文華酒店對出,沿干諾道中往金鐘推進。

~ [即時](17:56)逾千名示威者留守在夏愨道與添華道交界,防暴警察在水馬內設置高台及在特首辦的平台上,不斷向夏愨道行車線上的示威者發射催淚彈。

Artwork introduction:

~ 1807 Central: Riot police are marching from Mandarin Oriental Hotel along Connaught Road Central towards Admiralty.

~ [Live] (17:56) Over a thousand protesters remain at the junction of Harcourt Road and Tim Wa Avenue. Riot police set up platforms behind water barriers and on the rooftop of the Chief Executive’s office. They are firing tear gas at protesters on Harcourt Road traffic lanes.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[文章 Article] [只限英文 ENGLISH ONLY]

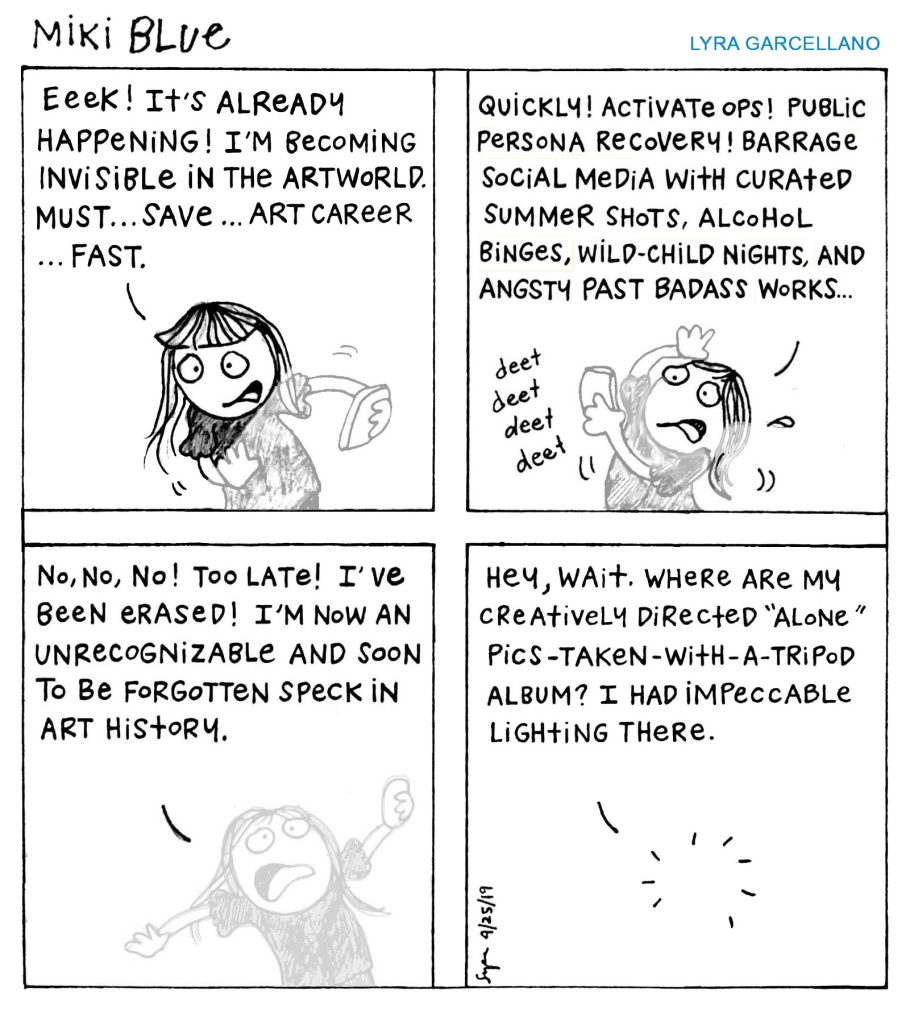

ZOMBIE SCROLLING, INFINITE LOOPING

—Lyra Garcellano

It isn’t surprising behavior whenever I wake up and automatically reach for my phone. While the purported goal is to check the time, I tend to get caught up, like many others, in scrolling mode. Before I’m conscious of it, I’m pulled into the whirlpool of other peoples’ narratives: photographs, stories, announcements, and feelings. If I don’t willfully detach myself, I would have fallen deep in this internet blackhole for an hour or two even before I roll out of bed. Except that, in this particular blackhole, nothing is dark or soundless; every bit of space is altered and punctured by everyone and anyone who wishes (or is made) to leave their imprints, or to make themselves heard.

More than a decade ago, the only instance when I spent an unusual amount of time online was when I played FarmVille––a game where the user manages a hypothetical farm. For a few minutes of the day, I busied myself planting carrots, strawberries, cabbages and all sorts of berries. After watering my crops, I was prompted by the game to step back––given that my imaginary produce needed growing time. On cue, I unplugged myself and did the stuff that no one had to care about (for example, my work). The next day my computer vegetables were just about ready to be harvested.

Nowadays, much of our waking (and even sleeping) life is tethered to the internet. Our relationship to the or a world is locked to the grid. Even if others say it doesn’t have to be, well, it is. Whenever we require any information big or small, we’ve been convinced that all we need are our Wi-Fi-connected phones to hop on search engines. It’s a plugged-in presence that has gone on infinite looping.

There is a constant stream of friends and strangers who announce their day-to-day (or hour-to-hour) happenings; being strung along by every posting has become the mood of our times. Lest we become ambiguous or forgotten, we’re almost terminally obliged to pepper and update the net with information on ourselves––our achievements, advocacies, skills, significance, and even best portraits. Zigzagging across time zones, we no longer only compete (or share) with people we know––we now wrestle for attention in a worldwide way. Our (varying) personas are performed, packaged and circulated like audition tapes, or as a contemporary version of our curriculum vitae. As cultural practitioners, we have taken on this routine based on the learned belief that not to be recognized online means to be booted out of some sort of production line, or potential future.

To offset feelings of invalidation caused by random metrics, suggestions of detoxification, hiatus, or cold-turkey quitting are thrown at everyone. The question is: Should we or can we take a break?

Will our present position grant us the same opportunity as others to attract the people whom we want to notice us? Are folks from the periphery even on equal footing with those from the designated center(s)? Despite attempts to keep up, are we ever seen? Seen-zoned, maybe?

Institutions, curators, funding bodies, fellow artists, critics, and the likes have been about searching the Internet––If I google your name, will I find something fascinating about you? To even get into this list of “people to look for” is to have prior or current visibility traction (inclusion in relevant literature such as catalogues, magazines, or websites that serve as records of one’s glorious career).

For those without the reach, and even if there is uncertainty on how strong (or how shaky) these bridges are, we rely on the good word of friends (or friends of friends) to help us distribute impressions of ourselves: our nicely curated photographic documentations, PDFs of downloadable texts, our zines, our drawings, our Instagram profiles, etc.

Ultimately, the effect of having to commit to this (net)work(ing), aside from the actual work off the net, is exhaustion.

To deal with weariness means to retreat. Naps are needed for the body and mind to recuperate if we are to continue treading the path of efficiency. But if a form of sleep is also a semblance of invisibility and dormancy, then metaphorically speaking, how long is the nap that one is allowed to take?

It’s easy to have long pauses if a person has the capacity to do so. Isn’t regrouping achieved by those who exercise degrees of privilege? If we are to count pennies and cents, we’d say the ones who are tenured in the academe can afford time off more than contractual employees who get paid only if they physically report to work. Failure to appear means not getting a salary at all. The same thing can be said about the art world and the web.

So, how much hermit-living can any of us manage (or sustain) in the art world? What becomes of those who, either by choice or out of frustration, are the reclusive (and soon to be the obscure) artists?

Those who refuse to be part of any social media or any online platform but can continue to function in this type of world are simply able to source the essentials––funds, life, time, everything else––elsewhere.

I’d like a ticket to that ‘elsewhere’.

*******

Meanwhile, I’ve taken to napping in the literal and figurative sense. Whether it’s a boost of power (or not), I just seem to doze off even amid working. Yes, the body is sending me a message. Being away from the ‘net noise’ seems more appealing now, although I still feel the weight of my sluggishness turning my future potential into a state of limbo. I can panic about it, but I can also decide to interpret it differently. In a hope-driven scenario, I’m out because it’s time I plotted my own kind of elsewhere.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[生活 Everyday Life] [中英雙語 ENGLISH & CHINESE TRANSLATION]

MOLILI MABE

MY OTHER LIFE

—written by Cédrick Nzolo in Lingala and French; English translation by Dominique Malaquais

Tia singa

Courant eza te

Changer phase

Benda courant

Zua neutre na mabele

Kobukana te pelisa mwinda

Words, all, to tell a disaster. An economic, a social, a political disaster.

Where I live, in the heart of Kinshasa, there is electricity three to five days a month. On those days, we have light for five to seven hours out of twenty-four. And so objects meant to make life easier—a stove, an ice box—become ornaments; they have no function; they occupy space; nothing more, nothing less. When light comes, it comes in the dead hours, between midnight and 6am. While my family sleeps, I write and draw. I live at night.

My life.

My other life.

Once, the situation was unacceptable. It is intolerable now.

Benda courant, or the art of making light where there is none. The principle is simple. You have no electricity. No one on your street or the three streets on either side does either. You all depend on a single switching station, and the cable that links you to it went up in flames last month. So you make friends with people four or five streets away, ask if you can tap into their lines. Some people just go ahead and do it, no questions asked. If you have a little money left over at the month’s end, you call an electrician. Today, I have 220 volts of electricity flow into my computer. I begin to type. Within minutes, the system collapses: 220 volts become 150, then 80, and, finally, 60. Dozens of folks have tapped into my line. It is the neighbor’s line, too. He has said yes to too many people: He needed the dough. The switching station can’t handle the additional load. And so, again, we move into darkness.

Half my life I have lived in this place where no one gives a shit about anyone else. The concept of working collectively loses meaning before it has had a chance to make a dent. We could all pitch in to buy a length of replacement cable. Sometimes we do. But just as fast, others come together and benda courant. Our light goes, our money—so scarce—too, and, as a result, our will to link arms.

Others think about other things. Some of us think about one thing over and over: this desk we sit at, the paper on which we set out to design objects and buildings and plans, using a candle stub to light our way. Meanwhile, our country exports electricity—sells it, for pity’s sake—because, yes, we have that much hydroelectric power and a government which cares that little.

Living in the dark, we have learned to wait even when there doesn’t seem to be anything left to hope for. And so we walk the streets at dusk and into the night. Some corners, some alleys we learn to avoid; past 8pm you meet pomba there: thugs, muggers. Still, it’s better to be outside—in the street, you can scream and drink and lie, talk and watch small dramas unfold; in the street, the walls of home can’t close in on you as you sit and wait.

In the street, we follow small moments of light:

Students travel miles to cluster under a lone halogen or neon lamp.

An incandescent bulb lights pieces of a wall; someone’s got power!

If it’s an LED, no one leaves ’til it turns off.

The occasional bar has an awning lit with colored microbulbs;

no reading here—

just beer, but at least you can see what you’re drinking.

Car headlights give a fizz-fast view of the way.

A flashlight is handy, but too often the choice is between batteries and food.

If you have one and you’ve been near a functional outlet in the last few days,

try your cell phone: turn it on and off fast for a brief look at the road ahead.

Fire up a match, a candle, a cigarette lighter;

see what you can see with the cigarette alone.

If you have several matches, the means, and the space, try a whole fire

(wood for flames, coal for embers).

A petrol lamp is good, but the price of gas is high these days. Learn to make the local variety. You’ll need an empty can (tomato sauce tins are good) or a glass jar (the ones they sell mayo in work well), a long wick, and a sliver of sheet metal to make a small stand for the wick; if you want to get fancy, add a bottle top to hold the stand in place.

Wait for a full moon.

Consider fireflies.

I write these words by the light of one candle. My translator sits thousands of kilometers away,

in a house blazing with lights she has forgotten to turn off.

Vie ezo leka pamba kaka boye.

Life is so damn short and the ways forward so few.

I wed faith with rage and push through to the next dawn.

In my other life.

This writing was originally published by Indiana University Press in Transition, Issue 102, 2010, pp.2–7.

POSTSCRIPT

MY LETTER TO DOMINIQUE MALAQUAIS

—Cédrick Nzolo

Dear Dominique Malaquais,

Today is the 24th of May 2023. You’ve left us already and I haven’t had a chance to see you or tell you that the project we worked on over ten years ago, fifteen years to be exact, will be translated into Chinese by someone I met when I was in London. Her name is Wing, and it’s a shame you won’t be able to meet her.

I only had the chance to visit London recently in April 2023, which is certainly why God decided to give me such an opportunity to look at this project differently. The lamps on which Molili Mabe was written are still present in certain corners of the Congolese capital where I live.

Yes, we haven’t seen each other for ten years, but you died too early. In the meantime my solar design projects have not succeeded because my mind was too busy trying to find suitable connections on a reliable network that was a little less saturated. There’s a lot to share that I won’t be able to do again, especially with you. All I have left is the memory of your name, because my friend immortalised your memory by naming his daughter after you. From now on, that’s all I am left with this publication Transition 102, the cover of which bears my photo with this subtitle: Let There Be Light.

I couldn’t find any other way of writing to you except this one, especially as my words will be translated into Chinese, so you’ll certainly get an echo if God allows. I said to myself that we could certainly pray for you if you believed in God, but alas, you always told me that God didn’t exist, and I looked for a thousand and one ways to tell you that God does exist and that he rewards those who seek him. You used to say, ‘Other people buy clothes but I buy books,’ and I have a gift of a design book from you in my little library.

In this semester of 2023, when I look back on my memories of these moments of work and especially since this Molili Mabe project, I haven’t done any photography because all my equipment has been damaged. I know I’m going to find the courage to start again, because the memory of my first publication is still there, even though it’s getting on in years, but it’s there, it’s going to be in Chinese soon and, God willing, the photos from My Other Life will also be making this tour in Asia. My writings travelled to the United States and twelve years later there was an exhibition in Paris with the project that will certainly be remembered by the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Kinshasa Chroniques, curated by you, Dominique.

When I see Mega Mingiedi, I remember everything, and as the past nourishes the present and allows us to dream of the future, I allow myself to dream better, with crazy ideas that only I can come up with. God gives me the strength for action and will. Sorry, I know you’re not a believer but, for me, God is very important because without him, there’s nothing.

As each day goes by, I came home seeing what the Molili Mabe project could have been—a field of solar panels, perhaps? But these days we’re talking about electric cars. So energy autonomy is a global issue, and is not just about lamps, but whole life systems.

Batika yo Dominique Malaquais

Nzambe ayebi esika ozali, esengelaki ondima ata nzambe kasi biso batu oyo totikali na mokili, toyebi valeur ya nzambe, soki apesa muana na ye Jesus Christ, ce que alingaki mpe obika ….

In memory of Dominique Malaquais.

Translated by Adeena Mey

Cédrick Nzolo, Wenze Masolo, 2008, photograph

Cédrick Nzolo, Walking Night, 2008, photograph

無光行履:我的別種生活

文:Cédrick Nzolo

譯:陳穎華

Tia singa

Courant eza te

Changer phase

Benda courant

Zua neutre na mabele

Kobukana te pelisa mwinda

用語言,或任何一切,訴說一場災難。一場關於經濟、社會和政治的災難。

我居於剛果共和國首都金沙薩的市中心。金沙薩平均每月只有三至五天有供電。在那些特殊日子,每天廿四小時當中,有五至七個小時我們有電開燈。諸如爐灶、雪櫃等等本來讓人生活輕鬆一點的器物,都變成了裝潢。他們佔據着空間,卻失去功能,僅此而已。有電可以開燈的時候,總是發生在午夜至清晨六時這段死寂的時間。其時,我的家人在睡覺,我自己卻在寫作和繪畫。我活在晚上。

這是我的生活。

我的別種生活。

曾經,情況差得難以接受。現在更是無法忍受了。

Benda courant,意旨在沒有光的情況下製造光的高深造詣,即汲電,又指出猫叉電。其原理簡單。試想像,你自己沒有電,你直屬的街道或街道兩旁其他三條街上均沒有人有電。你們所有人都依賴着這麼一個配電站,而連接你家和配電站的電纜在上個月着火了。所以你跟四、五條街以外的人交了朋友,你問他們,可不可以讓你接上他們的線路。有些人甚至不會問,直接去做了。如果到了月底,你還有點餘錢,你會打電話給電工。比如今天,我有220伏特的電壓流入電腦。我開始打字。然而,不過幾分鐘,系統開始衰竭,電壓由220伏特減至150,然後是80,最後只有60伏特。看來不少人接上了我的線路。我的線路又是鄰居的線路。看來他對太多人示好了,我明白他需要錢買麵包。配電站無法處理這些額外的負載。因此,我們再次進入黑暗。

我用了半輩子生活於這個沒有人會在乎其他人的地方。集體工作的概念,在它有機會產生任何影響之前,已經意義盡失。我們其實可以集資,去買一段電纜作替換。有時我們真的會這樣做。但同時,其他人會迅速聚集一起,Benda courant,出貓。於是我們的燈一一熄滅,於是我們本來已甚稀缺的金錢也隨之消失。如此,我們的合作意欲才蠢蠢欲動。

我們當中,有人有其他想像。有些人一再思考同一件事:我們依靠燭光去找出路,去照亮跟前的桌子,也照亮那些用來設計器物和建築物,以及書寫計劃的紙張。可是,與此同時,我們的國家卻出口電力——出口還是出賣?基於憐憫?——是的,我們有足夠的水力發電能源,配上一個漠不關心國民的政府。

活在黑暗之中,我們學會等待,即使這裏似乎沒有任何希望。我們在黃昏的街頭行走,直至黑夜。我們學會避開某些角落、某些小巷。因為晚上八點以後,你會在那裏遇到pomba,即狂徒、搶劫犯。儘管如此,還是待在外面最好。起碼在街頭,你可以尖叫、喝酒、撒謊、聊天,又或者待生活戲劇上演。起碼在街頭坐着等待時,家中牆壁無法靠近無法埋葬人。

在無數個街頭,我們追隨微弱的光:

學生徒步跋涉數英里,聚集在某盞鹵素燈或霓虹燈下。

某鎢絲燈泡照亮了一面牆;有人有電!

若果它是盞LED燈,沒有人會在它熄滅之前離開。

偶爾營業的酒吧,有個用彩色迷你燈泡點亮的遮篷。

此處無法閱讀——

只限啤酒,但至少,你可以看見自己在喝甚麼。

汽車車頭燈提供瞬間道路視野。

電筒是方便,但你往往要在電池和食物之間作選擇。

如果你有部手機,並有幸於近來數天在通電的插座充了電

可以試試快速開關手機,看一眼跟前的路。

燃點火柴、蠟燭,亮打火機;

或看香煙自己可以照亮多少。

如果你有數根火柴,有資本和空間,可以試試生個火

(以木生火,薪柴為燼)

汽油燈是不錯,但最近汽油價格相當之高。若想學習製作當地版本的燈,你需要一個空罐(番茄醬罐頭是個好選擇)或者一個玻璃樽(蛋黃醬樽會適用)、一根長燈芯,以及一小塊用來做燈芯支架的金屬片。如果想花俏一點,可以加個瓶蓋來固定支架。

或等待滿月。

或考慮一下螢火蟲。

我依靠一支蠟燭的光,寫下這些文字。而我的譯者在數千公里之外,

她在燈火通明的房間裏,忘記了關燈。

Vie ezo leka pamba kaka boye

人生很短,但前面可見的道路如此渺茫。

在我的別種生活中,

任信仰與憤怒,伴我堅持到下一個黎明。

【本文原刊於印第安納大學出版社《Transition 過渡》期刊,2010年第102期,第二至七頁。】

後記

致DOMINIQUE MALAQUAIS

文:Cédrick Nzolo

譯:陳穎華

親愛的Dominique Malaquais:

今天是 2023 年 5 月 24 日。你已經離世,我們沒能再聚,我更沒法告訴你,一位我在倫敦認識的朋友穎華,她會把我們在十多年前(準確地說是十五年前)的合作翻譯成中文。遺憾你們沒法相識。

直到今年四月我才有機會到訪倫敦。上帝自有安排,讓我以不同的方式看待往日的作品。我仍然居住剛果首都,那些在〈我的別種生活〉中記下的燈光,至今仍在城中某些街角可見。

我知道我們有十年沒見了,是你離世得早。我的太陽能設計項目尚未成功,只怪自己精神太緊張,終日不斷尋找可靠又未完全飽和的網絡。我有很多東西想要和你分享,但現在不可能了。朋友為他的女兒取了你的名字,藉此延續對你的思念。而我自己對你的回憶,就只剩下《Transition 過渡》第102期這本刊物了。封面圖片是我的攝影作品,配上標題「Let There Be Light 如初之光」。

除了這裏,我找不到其他方式可以寫信給你。我說過的話會以中文呈現,如果上帝許可,你定會收到訊息。我對自己說,如果你相信有上帝,我們便可以為你祈禱,但你總是告訴我,上帝並不存在。我嘗試用一千零一種方法說服你,上帝存在並且會賜予尋求祂的人。而你只說道:「別人買衣服,我買的卻是書。」我的小小圖書館裏,就有一本你送給我的設計書。

在2023年的這個學期,我問自己該如何回顧這些往日的創作時刻呢?尤其是自從〈我的別種生活〉以後,我再沒有拍過任何照片,因為我所有的拍攝裝備都壞掉了。我知道自己會找到重新開始的勇氣,因為即使許多年過去了,那個首次出版發表文字圖片的記憶仍在,而它很快就會有中文版,上帝保佑從前的照片也會踏上這趟亞洲之旅。我的書寫最初漂洋過海走到美國,然後十二年後,照片在巴黎博物館Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine的展覽「Kinshasa Chroniques 金沙薩紀事」( 由 Dominique 你策劃)中展示。這些都是值得銘記的時刻。

只要與Mega Mingiedi 見面,我便記起所有一切。所有的過去都滋養着現在,並讓我們想像將來。我容讓自己發更好的夢,追尋着只有我才能夠擁有的狂想。我相信上帝賜予我行動和意志的力量。對不起,我知道你不是信徒,但對我來說,上帝真的非常重要,沒了祂所有東西都不存在。

日復一日,我回到家中便會想,〈我的別種生活〉可會是甚麼,也許是一大幅太陽能電池板?但最近我們談論的卻是電動汽車。能源自主畢竟是個全球性問題,它指的不只是電燈,而是整個生態系統。

Batika yo Dominique Malaquais

Nzambe ayebi esika ozali, esengelaki ondima ata nzambe kasi biso batu oyo totikali na mokili, toyebi valeur ya nzambe, soki apesa muana na ye Jesus Christ, ce que alingaki mpe obika ….

懷念 Dominique Malaquais。

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[日常 Around Town] [只限英文 ENGLISH ONLY]

Banana and other fruit boxes in Peckham, London, 2022. Photo by Wing Chan

BANANA BOX BEARS

—Wing Chan

My curiosity about banana boxes is growing. I have been looking out for banana boxes for about a year. I have seen them in Kilburn High Road food and vegetable stalls and Peckham Rye fruit markets in London, flea markets in Berlin and Kassel, and along the streets of Bolzano when I was on my way to visit a David Medalla retrospective exhibition in the summer. Wherever I go, they are there waiting to catch my attention. They have become my best travel companions.

A banana box bears holes: a bigger hole on its end panels that functions as handles; two small ones below it for ventilation. Sometimes there are ventilation holes on the side panels, too. From the top, there is one large opening. In other words, a banana box does not conceal. It is always open.[1]

My interest in banana boxes began at the Offprint London book fair in May 2022. The publishing studio I am working at had a booth next to the Paris-based After 8 Books and Leipzig-based Spector Books. Two of Spector’s cartons arrived belatedly after the fair’s official opening hour. I noticed instantly from its design that they were banana boxes. The vibrant banana image on the cartons made them hard to be mistaken. Picturing tennis players munching on bananas during their breaks in between long matches, which is not unlike the level of carbohydrates and labour required for participating in book fairs, I pointed to the cartons and asked across the table if they were still fresh to eat. My Spector friend laughed. She started unboxing and told me about their tradition of collecting banana boxes from local supermarkets and using them to ship books to international book fairs across the globe.

They are strong, she said, meaning banana boxes resist shocks and protect the books and the people who handle them. I liked it. I was also interested in how, because of the special design of the ventilation holes, it created this imagery of the books needing to breathe. The box and the books inside cannot but confront the elements in the air. Moreover, banana boxes, no matter what brand, share similar sizes and are thus stackable. This explains why they often come in masses and are rarely spotted alone. There is a kind of solidarity in this form. To witness how banana boxes contain books and to understand the functions of their various design features, I began to think of the banana box as a timely metaphor: one to bring the role of book editors, writers and translators closer to that of the figure of ‘cultural workers’.

In my journey of exploring banana boxes, I encountered enormous deaths. This wave of death came from the earthquakes and aftershocks that hit southeastern Turkey and northern Syria in February 2023. While tectonic movements are natural processes, the shock-resistant capacity of buildings and the reservation of evacuation lands are controlled by humans and the state. In the case of Turkey, the state set new construction standards after the historic devastation of the Marmara Earthquake on 17 August 1999. Yet, in the following two decades, buildings were developed for economic growth at a speed too fast to observe disaster readiness. Designated evacuation points were sold off by the Recep Tayyip Erdogan administration to developers for shopping malls, business centres, and parking lots. The social reality in Turkey was in violation of the approved roadmap, the National Earthquake Strategy and Action Plan 2012–2023,[2] which sought to make the country earthquake-proof by 2023.

Throughout the cause of the roadmap and upon anniversaries of the 17 August 1999 earthquake, the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects (TMMOB) warned repeatedly in press statements that millions of structures in Turkey were unsafe and at risk of collapsing in the next big earthquake and that earthquake evacuation areas should not be repurposed, contending the authorities’ care for profits more than human life.[3] Indeed, the Erdogan administration had excluded TMMOB and its affiliated Chambers from involving in the planning, design, production, and supervision processes of public and private development projects since 2013, which was equivalent to the state’s eviction of the public control mechanism. When the earthquakes hit Turkey on 6 February 2023 and took nearly 50,000 lives, the 1999 disaster and the TMMOB’s repeated warnings became haunting prophecies of the colossal loss of life that could have been avoided if the state were not indifferent.

Two days after the 2023 quake, activist Ayşe Çavdar recounted her experience witnessing the state’s negligence at the post-disaster sites in 1999.[4] When the state was not present, there were people: civil society emerged. She was part of the coordinated civil effort to aid the rescue and relief work. It was in that post-disaster solidarity that a generation of leftist thinkers and activists emerged. Many of them later studied Turkey’s urban development policies and became activists fighting against the state and market forces in resisting the redevelopment of Gezi Park, one of the last open green spaces in Istanbul, in 2013. They occupied the Gezi Park and the adjacent Taksim Square. Many of these activists were forcibly disappeared, tortured, or jailed. The same question of ‘where the state is’ was raised again and repeatedly in the recent 2023 disaster.

Thinking along these lines, to be a socially conscious artist or practitioner in arts, we must turn ourselves into cultural workers. To be a cultural worker is to situate one’s work outside pure individual achievement and within the field of political struggle. This ideological position allows an individual to declare that collective political education, social conditions study, and cultural training are part of your practice.[5] How banana boxes are equipped with handle holes, which speaks to manual labour, can be likened to a cultural worker’s purpose to be in contact with the masses and build resistance against exploitation.

A banana box is an enclosure with openings. Imagine the banana box with ventilation holes being a structure of civil society that defends breathing spaces for its inhabitants, and which simultaneously brings itself to interrogate the conditions, environmental or socio-political, of its own existence. Identifying the class of each box of bananas that suggests their relative economic values and the refrigerated container that offers fresh air supply or controlled atmosphere would be the cooperative task of a truck of banana boxes.[6] A raised awareness of the journey would help the banana box monitor any manipulation legitimated by a state and market forces.

This is how the banana box shapeshifts into the figure of a civil society carried, transported, and shipped away by a cultural worker. And if political prisoners are often only allowed for books and writing materials as limited channels for education and expression, the textual production of cultural workers contributes greatly to solidarity and change.

Artist Merve Ünsal wrote about Taksim Square in the article with the breath of the wind like a small cloud. Ünsal produced a two-channel radio transmission work, With the Wind (2021), that transmitted sounds of air passing through repurposed ventilation pipes alongside collated audio recordings from media about Taksim and its surroundings. She wrote,

… Near an increasingly policed Taksim Square, I hold on to the narratives and whispers about what the square has been and what the square can become, knowing and appreciating that there is no linear text that can be written about this place; the best I can hope for is to hold my ear against the ground, the trees, the walls, the winds that carry, the winds that erode.[7]

Taksim is only covered briefly, but it is present throughout the writing. The text begins with the loss of a grandmother, and with that it introduces the wind as a howling force of penetration that can shake and tremble a sheltering structure. The other side of the wind is a breathing body which can hear the utterances—narratives, accounts, and testimonials—that pass through it. The wind becomes an analogy of listening, sitting with pain, and staying with the rattle, which is what Ünsal believes that an artistic practice can hope to achieve.[8] I think of a banana box that bears holes and collects what the wind has been attuned to in its journey of travelling across borders.

Ünsal is also a translator for The Dumpling Post, a small-run publication released in October 2022 reflecting on The Kayseri Dumpling Festival in late 2019. The Festival was a reaction to the state’s banning of an international science conference titled ‘The Social, Cultural and Economic History of Kayseri and the Region’. The conference was supposed to be organised by the Hrant Dink Foundation in 2019 to examine histories of different cities of Anatolia on the axis of memory and reconciliation. The staff, who often worked within academic spheres, instead found themselves in the position to learn how to coordinate a dumpling festival for over 500 people as an act of creative resistance against the oppressive regime. The questions that they asked before venturing into this journey were: ‘How effective is responding [to the regime] with a written statement in today’s world? And how can we build solidarity? In the face of this prohibition, how can we heal the despair we find ourselves in?’[9]

A concrete picture of what collective action and education, such as a dumpling festival, can do is given by lawyer, writer, and human rights activist Fethiye Çetin on The Dumpling Post. Any paraphrasing would obscure its texture and thus, I provide the following long quotes from Çetin.

Oppressive regimes not only violate our rights but also take away our capacity to imagine new and creative forms of resistance. Many of us are focused on standing our ground, at whatever cost, rather than strengthening solidarity and challenging the oppression by producing and acting together. While it is important to stand firm, I think it is even more important to develop ways to overcome a crisis in order to move forward… The implicit message of this festival was: ‘I have rights that are independent of what the state recognises and permits, and I am using my right to exercise these rights.’ The justice of the law ‘granted’ by the state was questioned, and the ban was challenged… The dialogue established that day over food allowed us to build new, solid friendships by shunning the identities imposed upon us and expanding the cracks in the artificial boundaries drawn between us.[10]

Çetin also wrote about a longue durée vision of resistance,

As humanity has shown, even thousands of years ago, remembering is justice, forgetting is injustice. While remembering, we also carve a mark on the present. Like any cut, it hurts, but let’s not forget that light also enters from there.[11]

*******

This writing was conceived at the conjuncture of my obsession with banana boxes, the Turkey-Syria earthquakes, conversations with Merve Ünsal via our mutual friend Özge Ersoy, the murder of Ericson Acosta, and the reading of Jose Maria Sison’s early writings in the sixties which were generously shared by Arianna Mercado and her friends whom I got to meet in London. All of these have helped me think about my role as a cultural worker in the publishing field and the formation of a civil society in Hong Kong and elsewhere. As I started writing ‘Banana box bears’, I began voluntarily translating Ünsal’s article on wind into traditional Chinese. There was an urge to swallow words as I felt the howling wind, as I hoped to be able to listen to stay with pain, as I internalised the banana box to bear holes, make room, and fight anxiety, and as I desired protection, collective political education, and solidarity. By the time Power Naps Post is released, Erdogan is re-elected as Turkey’s president. It becomes even more urgent to hold space for writing.

[1] Further research taught me comprehensive knowledge about the shape of the banana box. packworld.com published a lengthy article on ‘hand holes’. This is the gist: “When a box is lifted via hand holes, the weight of the contents is supported by the bottom of the box. If not adequately secured, the bottom will give. This means that its contents will fall through, resulting in content damage and possibly personal injury. Even when the bottom is adequately secured, if there is not enough board between the hand holes and the top of the panel, the board can rupture from the force of lifting, likely causing the handler to drop that end of the box.” The breathing holes, however, did not receive equal attention from packing professionals and industrial experts. The search brought me, instead, to metaphorical information about ‘box breathing technique’ to fight anxiety. I kept both for mental notes.

[2] See the strategy and action plan in English: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b44c2b34.html.

[3] One of the press statements of warning made by TMMOB before the 2023 earthquake (17 August 2021): https://www.tmmob.org.tr/icerik/17-agustos-depreminin-22-yilinda-bir-kez-daha-uyariyoruz-bilimin-teknigin-ve-doganin-sesine. TMMOB’s press statement released after the 2023 earthquake (27 February 2023): https://www.tmmob.org.tr/icerik/tmmob-iskenderun-ikkdan-6-subat-depremi-aciklamasi. TMMOB’s investigation report on the 2023 earthquake (10 April 2023): https://www.tmmob.org.tr/icerik/tmmob-tbmm-tarafindan-kahramanmaras-merkezli-depremlerin-sonuclarinin-tum-yonleriyle.

[4] See the free press: https://medyascope.tv/2023/02/08/ayse-cavdar-ve-aysuda-kolemen-ile-genis-zaman-107-nerede-o-devlet.

[5] Taking this idea from Ericson Acosta’s articulation of cultural workers. Ericson Acosta interviewed by Jonas Staal, ‘I Am a Cultural Worker’, in New World Academy Reader 1: Towards a People’s Culture, Utrecht: BAK, 2013, pp.96–107. See https://www.bakonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/NWA-Reader-1.pdf.

[6] As of May 2023, unripen bananas imported into the UK must follow the marketing standards set for bananas by the European Union in 2011. Bananas are classified into three classes: ‘Extra’ class, Class I, and Class II, with lower prices paid for the latter. See Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1333/2011: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:336:0023:0034:EN:PDF.

[7] See Merve Ünsal’s full writing: https://m-est.org/2022/04/12/with-the-breath-of-the-wind-like-a-small-cloud.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Dumpling Post had a small print run of 2,000 and was distributed at the 17th Istanbul Biennial (17 September–20 November 2022). Hrant Dink Foundation and 23.5 Hrant Dink Site of Memory on the civil society, “Our first reaction was to put forth our reaction to this, release a press statement and make an announcement, and, in fact, we did inform the public of our reaction. Then we asked ourselves the following questions: How effective is responding with a written statement in today’s world? And how can we build solidarity? In the face of this prohibition, how can we heal the despair we find ourselves in?” See ‘About Dumpling Post’, in The Dumpling Post, Turkey: Hrant Dink Foundation, 2022, p.3.

[10] Fethiye Çetin, ‘Thoughts on the Dumpling Festival’ in The Dumpling Post, Turkey: Hrant Dink Foundation, 2022, p.7. Translation by Ayla Jean Yackley.

[11] Ibid, p.10.

The first edition of this writing was published in no exits, issue Vessel, June 2023.

Banana boxes in Bolzano, Italy, 2022. Photo by Wing Chan

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————