Little by little and then all of a sudden, in the two months between the original opening date of this exhibition and the actual date, all events merged into one event, familiar in its conjuring of sickness, death, and our fear of others, and yet awesomely new in its might, effortlessly stopping the unstoppable wheels of our world. There are many things that will change against our will and many things that we must change ourselves. Changes that were already on the way, in how we work, pay, and value each other, our being together, and the presence, the signs, the gestures, and the touching in the art world will find perhaps a chance in the ruins of any certainty to arrive faster. Others, we will have to summon and midwife ourselves, working together for the ruin of the old and ruinous. How we will succeed in this, and thrive in the impoverishment that looms over our future, in the severed and narrow parishes we have been forced into, for months, maybe more, we are yet to see.

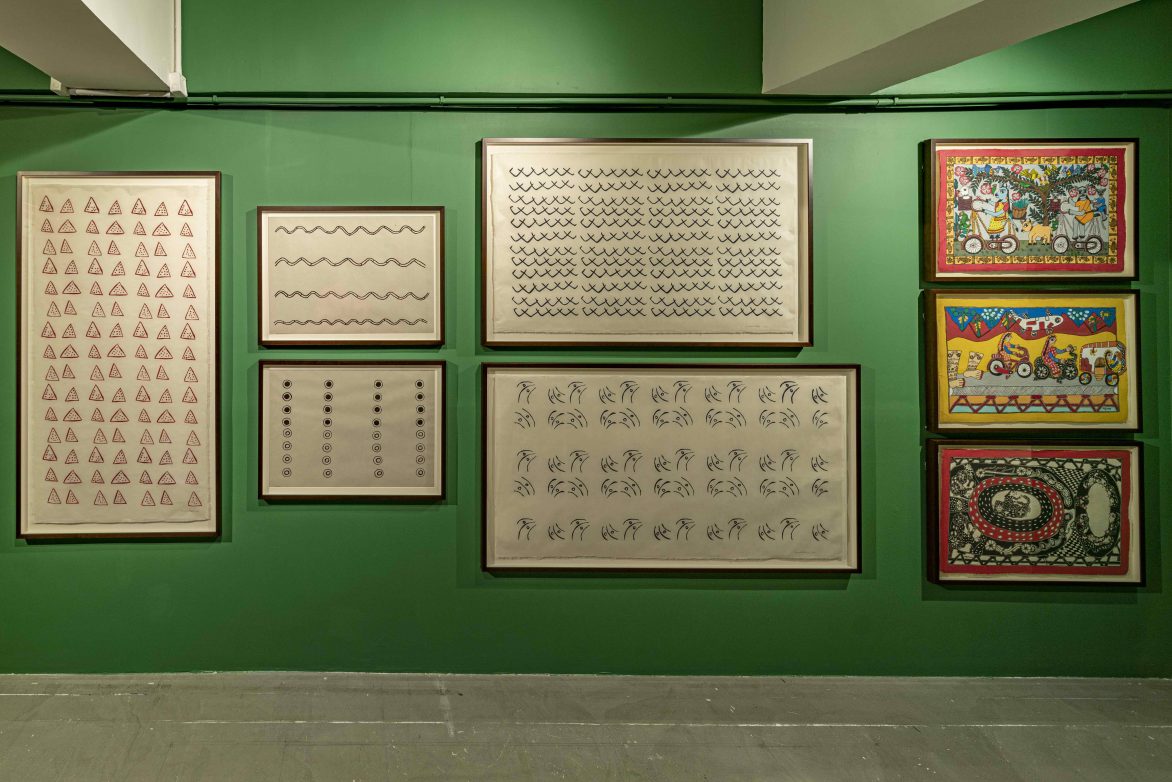

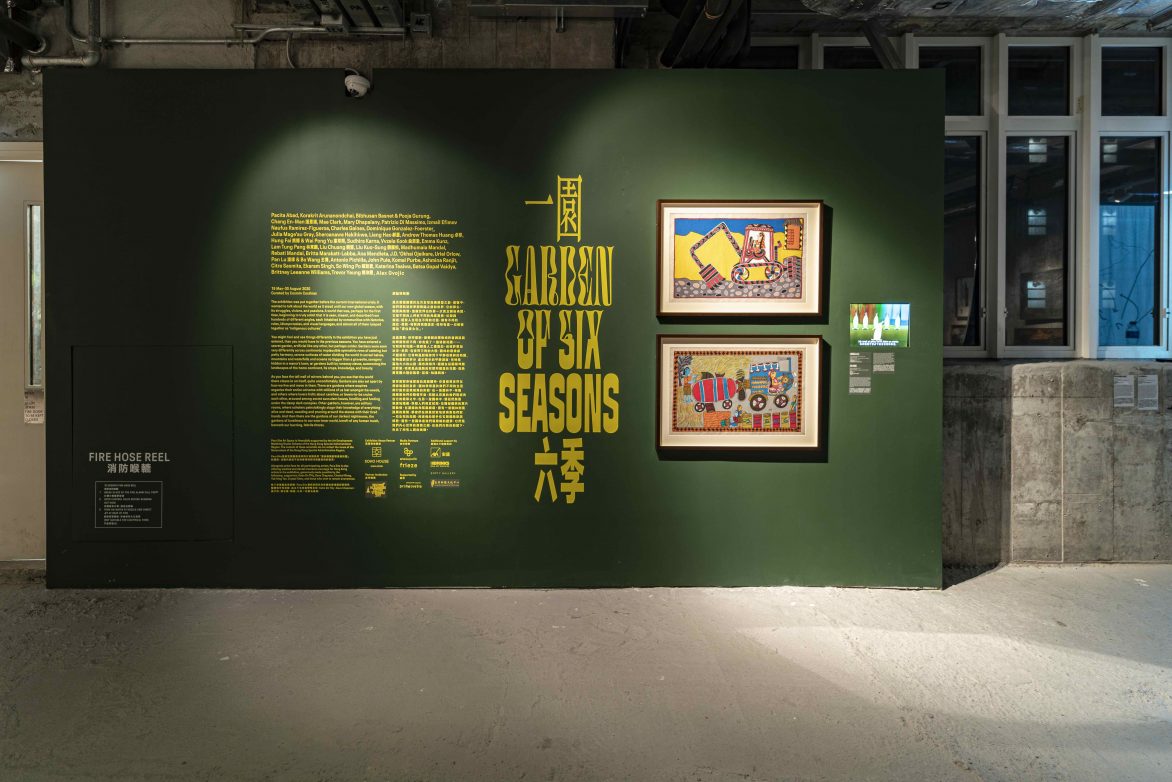

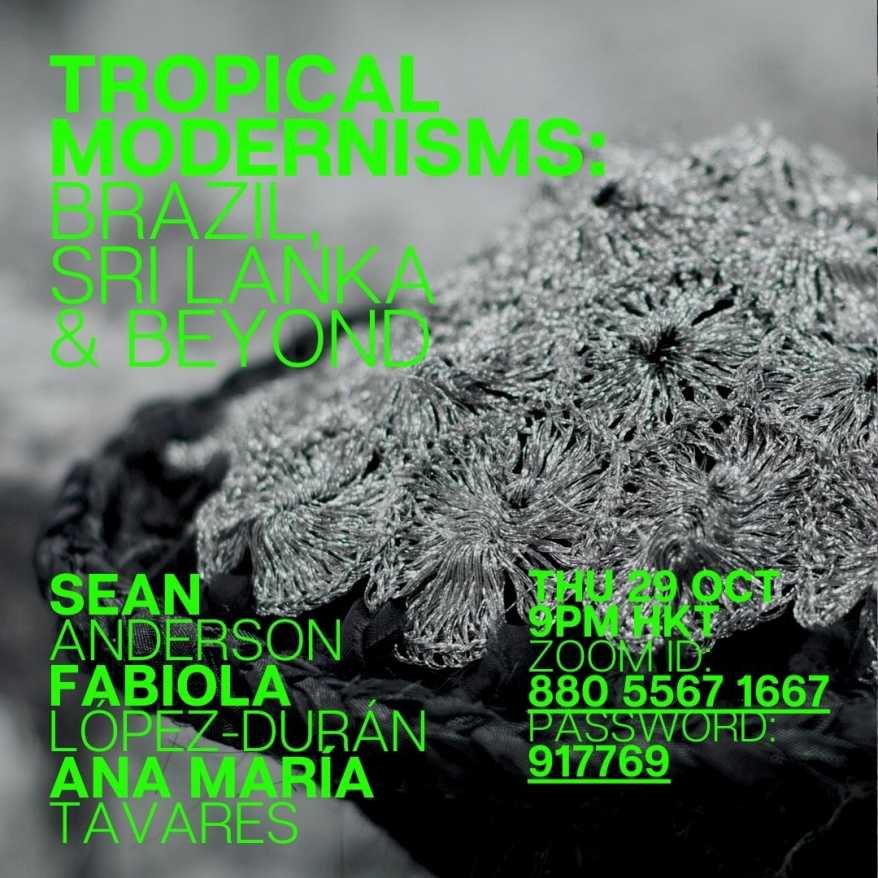

This exhibition was made with a certain desire and privilege of embracing the world. Without melancholy, from the fortunate gaze of Hong Kong, where we can open to the public with a certain sense of safety, we can now perhaps reflect on what became obsolete about this exhibition, in the two months that have passed. The art world of the past allowed many artists without much privilege the conversations, mobility, knowledge, and transcontinental intimacy often reserved for oligarchs. This exhibition was a product of that, conceived with the help of our artist colleagues in Kathmandu, as a precursor to the Kathmandu Triennale, which we symbolically removed from the ill-fated Gregorian calendar year of 2020 and restored in the ancestral indigenous Nepali system of counting the time. This system registers the 7 months from now (seemingly an eternity from our vantage point), when at the time of this writing we are still planning to open the Triennale, as 2077. In the exhibition, we wanted to talk about the world as it stood until this recent season, with its struggles, visions, and passions. A world that was, perhaps for the first time, beginning to truly admit that it is seen, dreamt, and described from hundreds of different angles, each inhabited by communities with histories, rules, idiosyncrasies, and visual languages, and almost all of them lumped together as ‘indigenous cultures’. This plurality was creeping into the way we were representing the world through art and this was one of the leading thoughts that organized the exhibition we were putting together. Alongside that nagging and perhaps obnoxious pretense of affecting change through our practice, which, until the end of last season, had been a central part of how so many of us saw our role in the world, even when such change seemed a monumental task. In this new season, change is happening above us, with frightening ease.

Like the whole exhibition, its title is obsolete in many ways. It is the name of a real garden in Kathmandu, better known by its other name, Garden of Dreams, built by a dynastic prime minister in Nepal, exactly 100 years ago. It was designed as an Edwardian English Neo-Classical Garden amidst Kathmandu’s urban fabric. The waves of change in the last century brought its six pavilions down to three. Climate change merged Kathmandu Valley’s famed six seasons into four. The Rana dynasty of the garden’s patron is long gone. So is the monarchy, swept away more recently by the revolution of this generation, the source of Nepal’s abundant critical energy that can teach us all so much.

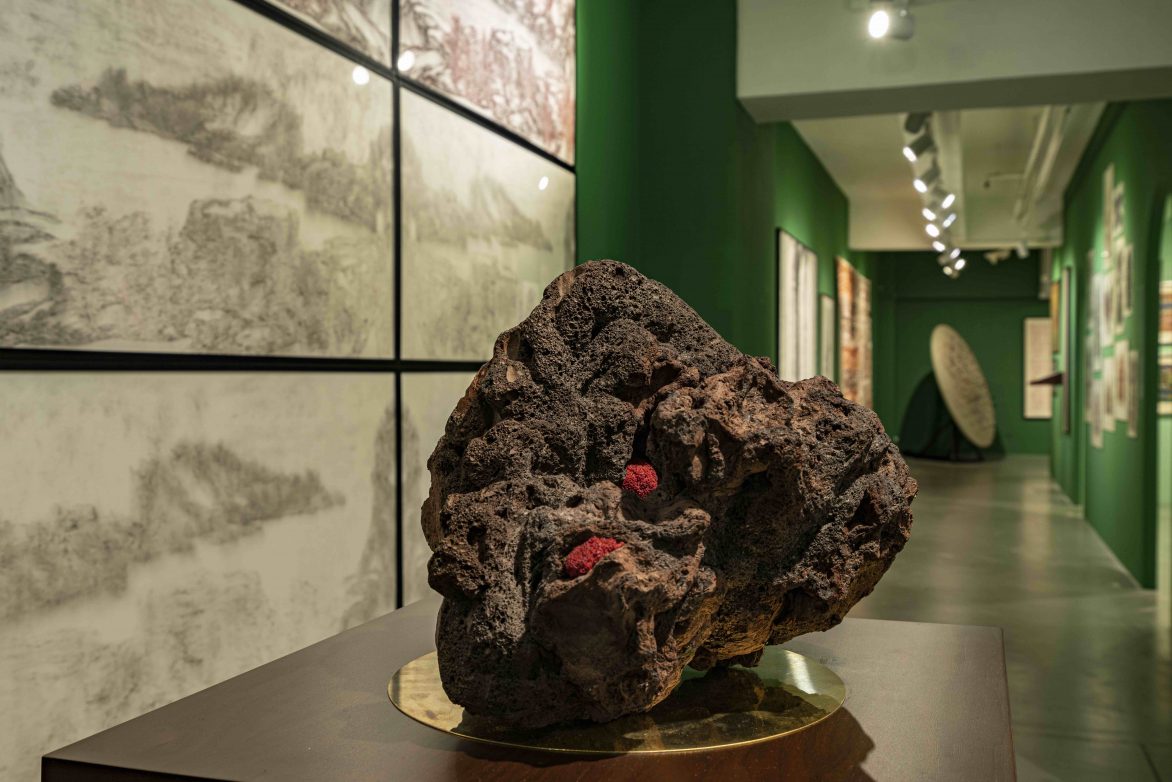

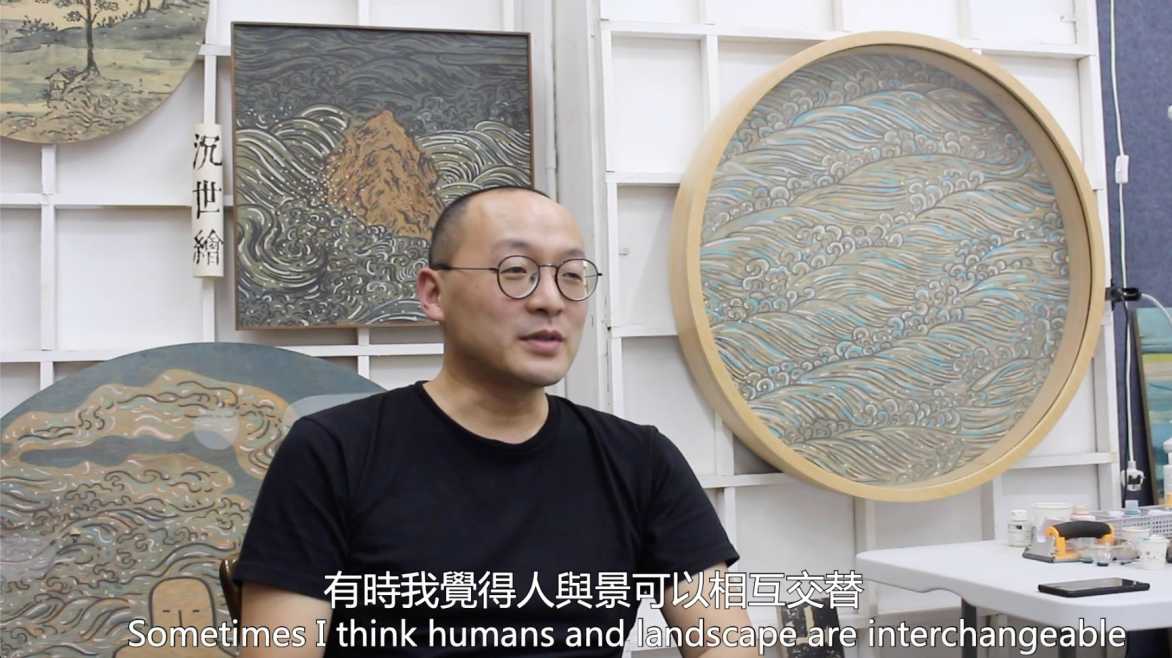

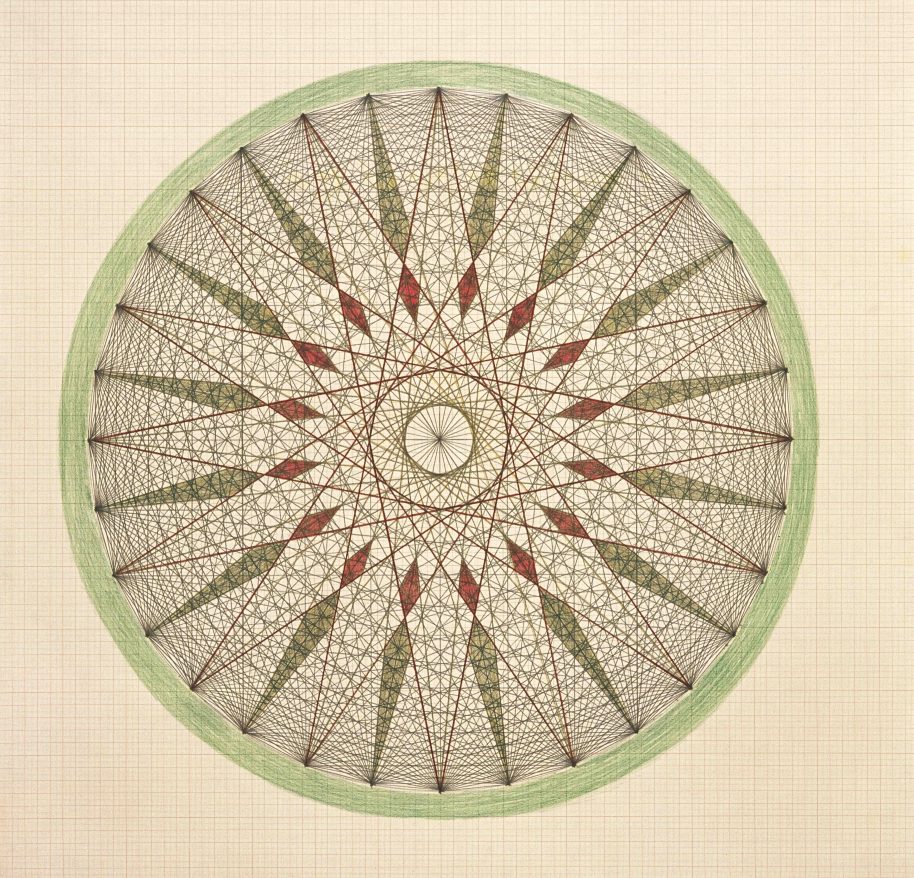

As you enter the exhibition, you might feel and see things differently than you would have in the previous seasons. At Para Site’s top floor, you will be drawn into an (almost) symmetrical architecture, with a darkened perimeter corridor enclosing a brighter space, a patio that hides perhaps an austere garden. Along this corridor, with an ease that might make more sense to you now, the artworks connect our bodies, their insides, the networked maps of our social worlds, and the cosmos with its frightening designs. You will encounter artists who have worked in different traditions, gongbi and xieyi, braidings of hair and pandanus, yet all of them of our time, on the cusp of seasons. Many of them harness the power of women to think about our world. The patio extends these axes, the (gendered) body, its microscopic interiors, its laterals in the social crust of the Earth and its higher place in the universe, each level populated by strangers and dangers, as seen through different traditions of healing and art. The very core of the exhibition is thus occupied by medical thinking, with its different cultural histories and understandings of where the disease nests, what is to be healed, what can be left untouched, and when to let go.

Downstairs at Para Site, the secrets in the back room might be more hidden than they appear at first. Even more, at the exhibition’s temporary station in Sheung Wan, you will enter a secret garden, artificial like any other, but perhaps more cold. Like the way medicine sees more than the inside of our bodies, and mapping the world draws both more and less than what really exists in the terrain, unseen by humans, gardens are themselves small visions of both a human organism and of the entire universe. Tending to a garden is akin to healing a body and to keeping a cosmic balance. But gardens were seen very differently across continents: implausible symmetric rows of calming but petty harmony, serene surfaces of water dividing the world in unreal halves, mountains and waterfalls and oceans no bigger than a gravesite, savagery hidden in a manor’s lawn, or gardens built by runaway slaves, summoning the landscapes of the home continent, its crops, knowledge, and beauty.

As you face the tall wall of mirrors on the longest side of the exhibition, you see that the world there closes in on itself, quite uncomfortably. Gardens are also set apart by how we live and move in them. There are gardens where empires organize their entire universe with millions of us lost amongst the weeds, and others where lovers frolic about carefree, or lovers-to-be cruise each other, aroused among secret succulent leaves, fondling and fucking under the damp dark canopies. Other gardens however, are solitary rooms, where scholars painstakingly stage their knowledge of everything alive and dead, weeding and pruning around the stones with their tired hands. And then there are the gardens of our darkest nightmares, the gardens of loneliness in our own inner world, bereft of any human touch, beneath our burning, febrile thorax.